Gabriella Garcia, “The Cybernetic Sex Worker,” December 16, 2021,

From e-commerce to streaming video to content creators, the internet as we know it was built on the back of sex work.1 From the web’s earliest days, sex workers’ labor enticed potential users to overcome the hurdles of expensive hardware and clunky interfaces. The promise of real-time erotic interaction drove consumer demand for faster modems, clearer webcams, and greater bandwidth. And, for better or worse, the adult industry’s technical and social innovations—including cookies, web analytics, affiliate marketing, and seamless online payments—demonstrated the commercial potential of a risky new technology.

Although these facts were widely reported at the time, contemporary accounts of the internet’s origins overwrite the stigmatized workers who made it desirable, accessible, and profitable. Such conspicuous erasure prompts pointed questions: Why is this undeniable history overlooked? Who does a sanitized narrative of technological development and adoption serve? As we grapple with profound shifts in the ways we live, work, and communicate, why would we ignore the people and communities who have navigated the internet’s potentials and perils from the start?

“Sex workers created the internet.”

Erin Fitzgerald et al., “Meaningful Work: Transgender Experiences in the Sex Trade,” 2015, 8.

Sex Workers Built the Internet asks what we can learn about the internet’s past—and its possible futures—when we listen to sex workers. An internet history that centers sex workers is necessarily multivocal, complex, and contradictory. It is a history in which revolutionary possibilities for solidarity and self-determination are inseparable from new forms of censorship, surveillance, and exploitation. It is a history that honors sex workers’ essential roles in developing and popularizing new technologies, while acknowledging the necessity and criminalization that drove them to early adoption. It is a prescient history; again and again, sex workers have been forced to deal with the internet’s contradictions well before everyone else, with the harshest potential consequences.

Most importantly, it is a history of the communal creativity, connection, and care that sustain the essential fight for a safer, freer, and more inclusive internet. Weaving together archival image research, oral history, and contemporary and historical writings, Sex Workers Built the Internet centers the voices and experiences of people whose identities encompass—but are not limited to—sex workers, artists, activists, organizers, and researchers to tell a story with urgent relevance for all internet users. As the accounts in the following chapters make clear, the statement that “sex workers built the internet” is undeniably true. But, more significantly, it is an invitation to listen to, learn from, and take action to support those who are most intimately familiar with the internet’s contradictions, and who are doing transformational work to make it more just for everyone.

An important note: The ways people define themselves and their work is diverse, meaningful, and politically charged. As the authors of Meaningful Work: Transgender Experiences in the Sex Trades explain,

“Sex work” is a broad term used to describe exchanges of sex or sexual activity. Sex work is also used as a non-stigmatizing term for “prostitution,” but in this report we use the term in its broader meaning. Using the term “sex work” reinforces the idea that sex work is work and allows for greater discussion of labor rights and conditions. Not every person in the sex trade defines themselves as a sex worker or their sexual exchange as work. Some may not regard what they do as labor at all, but simply a means to get what they need. Others may be operating within legal working conditions, such as pornography or exotic dancing, and wish to avoid the negative associations with illegal or informal forms of sex work. In addition to the exchange of money for sexual services, a person may exchange sex or sexual activity, or things they need or want, such as food, housing, hormones, drugs, gifts, or other resources.2

Although this publication, and many of the individuals whose words are gathered here, use the term “sex worker” to describe themselves, some do not. For this reason, those quoted are described in their own words throughout, and their identities are never assumed.

Exploitation / opportunity

Expl**tat**n/ Opp*rt*n*ty

From the internet’s beginnings, new technologies facilitated theft and exploitation — but also created opportunities for workers to take control.

Stolen porn fuels early internet expansion

Sexy images enticed users to wrestle with clunky, expensive technologies, fueling development, investment, and growth.

Benj Edwards, “The Never-Before-Told Story of the World’s First Computer Art (It’s a Sexy Dame),” The Atlantic, January 24, 2013.

Historian Mar Hicks, quoted in Linda Kinstler, “Finding Lena, the Patron Saint of JPEGs,” Wired, January 31, 2019.

The internet is notorious for facilitating access to stolen porn; however, technologists have helped themselves to women’s images and labor long before the web existed. The first known image of a human on a computer screen was a woman’s reclining silhouette, programmed with punch cards by an anonymous military engineer in the mid-1950s from a pin-up illustration.1 A stolen erotic photograph has been woven into the technologies that allow images to move through computerized networks since 1972, when a team of engineers at USC scanned model Lena Forsén’s Playboy centerfold from the shoulders up. Forsén’s photograph, endlessly reproduced to this day, became the uncredited and uncompensated industry standard for testing JPEG compression algorithms—just as women started getting pushed out of the computing industry.2

1972

Lena Forsén’s scanned Playboy image

Forsén’s endlessly reproduced image has become a benchmark for assessing digital image processing algorithms. In this example, it is used to demonstrate “transformations, edge detection, thresholding” on a computer science syllabus. Via professor Bognár Gergő’s “Image and Signal Processing” syllabus. Source

Kinstler, “Finding Lena, the Patron Saint of JPEGs.”

David C. Munson Jr., “A Note on Lena,” IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 5, no. 1 (January 1996): 3.

“Every Picture Tells a Story,” Claremont McKenna College Newsroom, May 2, 2013.

Lorna Roth, “Looking at Shirley, the Ultimate Norm: Colour Balance, Image Technologies, and Cognitive Equity,” Canadian Journal of Communication 34, no. 1 (March 2009): 125.

Although Forsén bemusedly embraces her legacy,3 women in computer science fields have long described the feelings of discomfort and exclusion her image evokes,4 and creatively protested its use. In a 2013 scientific paper, two computer science professors used a photograph of beefcake model Fabio to demonstrate their image processing algorithms (notably, they obtained his consent),5 while the promotional website for the 2019 film Losing Lena challenged tech industry viewers to sign a pledge to “remove one image to make millions of women feel welcome in tech.”6

Despite decades of protest, Forsén’s experience has been repeated. In a 2019 Wired article, journalist Linda Kinstler placed her in a “sisterhood of muses” that includes pop star Suzanne Vega, whose 1987 hit “Tom’s Diner” was used to develop MP3 audio compression.7 Vega’s voice was to MP3s what Forsén’s face was to JPEGs, and where Forsén was eventually dubbed “The First Lady of the Internet,” Vega’s audio (appropriated without her knowledge) earned her the title “Mother of the MP3.” And, although they were compensated for their work, others—including Shirley Page and her “Shirley card” predecessors, whose images were used to calibrate color film, and voice actor Susan Bennett, whose voice was used for Siri’s initial incarnation—attest to the racialized and gendered power imbalances at the core of technology and imaging industries.8

ASCII porn is credited as being the first form of pornography sent across the internet.

2006

ASCII porn gallery

Although ASCII porn predated the internet, it remained popular well into the era of Web 2.0. Examples here from the now-defunct asciiporn.us, “Just another ASCII porn weblog.” Source

Samantha Cole, “ASCII Porn Predates the Internet But It’s Still Everywhere,” Vice, January 14, 2019.

Unsurprisingly, then, the legacy of Lena Forsén’s uncompensated erotic labor haunted the internet from its inception. The telephone lines connecting early computer users in the 1970s and ‘80s were far too slow to transmit photographs, but message board contributors created ASCII art—a successor to typewriter art—as a way to share images made from keyboard characters and encoded into fast-loading text files. And many of those images depicted professional models. In Vice, journalist Samantha Cole spoke to an ASCII artist who explained that they “got into converting playboy girls into textmode [like ASCII, PETSCII and teletext].”9

Suzanne Stefanac, “Sex & the New Media,” New Media, April 1993, 39.

By the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, Usenet and bulletin board system (BBS) users began hosting and trading photographs in addition to ASCII porn. Once skillful, labor-intensive ASCII translation was no longer necessary, the quantity of stolen porn circulating through BBS groups exploded. Writing in 1993, a journalist attributed this shift (with a healthy dose of aesthetic distaste) to hardware and software advances:10

With the advent of inexpensive scanners and the handy GIF format, a flurry of poorly resolved cheese cake, beefcake and worse began clogging the up and download lines of major bulletin boards.

1993

Download menu of the Event Horizons bulletin board service

The Joy of Cybersex, a guide published by a producer of game strategy guides, shows curious would-be users an erotic BBS interface. Source

“Hey, I’ve seen this GIF before…” PC Mag, October 26, 1993, 467.

Like Forsén’s Playboy centerfold, many of the erotic images moving through BBS groups were scanned from magazines. A 1993 advertisement for Gourmet Gallery BBS in PC Mag attempted to differentiate itself from other boards, boasting that their images are “100% original and never-seen-before.”11 In 1992, journalist Gary Wolf reflected on the culture of rampant theft in Future Sex, a technology and erotica magazine:

Competition among boards is fierce. Since digitized images can be copied indefinitely with no significant loss of quality, dirty pictures circulate quickly through interlocked networks, and a sequence of popular photos will crop up in many places at once.

Margot Harris, “Terabytes of Stolen Porn from ‘OnlyFans’ Were Leaked Online,” Insider, March 2, 2020.

Online theft, of course, remains a serious problem for sex workers, with dire consequences that can go far beyond the financial.12

Porn performers were at the vanguard of the era of personal websites, including the whole idea of having a personal website with a membership option as an individual brand.

Early innovators move online

Sex workers with technical expertise and startup capital invented new ways to use incipient networks and make money online.

Patchen Barss, The Erotic Engine: How Pornography Has Powered Mass Communication, from Gutenberg to Google (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 2010): 122.

In the internet’s earliest days, sex workers were largely not profiting from their labor, even as the promise of their (often stolen) images sold computers, modems, hard drives, scanners, and BBS fees.13 But this began to change as workers with some combination of name recognition, investment capital, and technical expertise came up with ways to charge web surfers to access their photographs.

As sex workers, we understood intuitively from the beginning of social media—maybe even from the beginning of the internet—that the reason to be online is to sell something.

Michael Brooks, “The Porn Pioneers,” The Guardian, September 29, 1999.

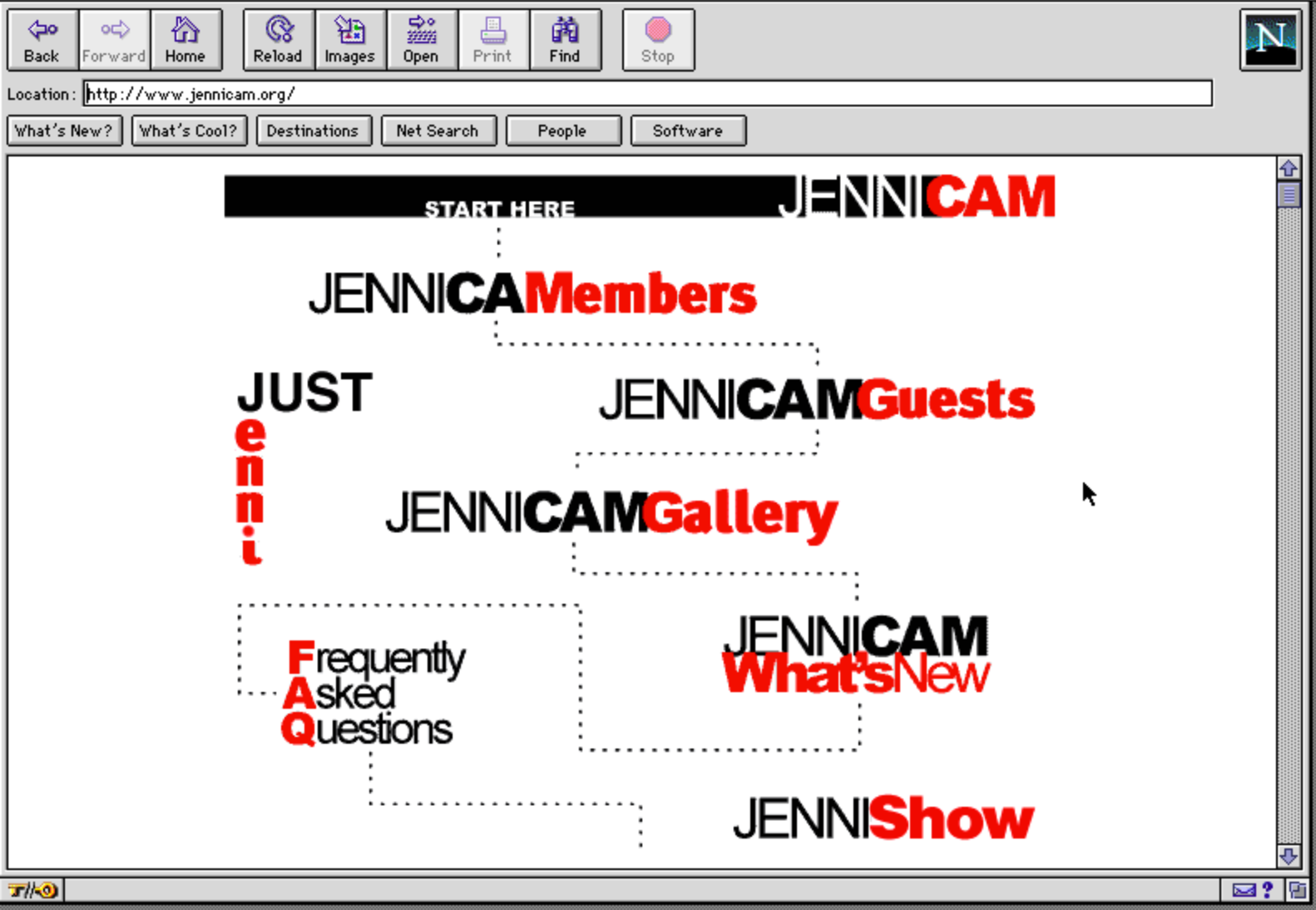

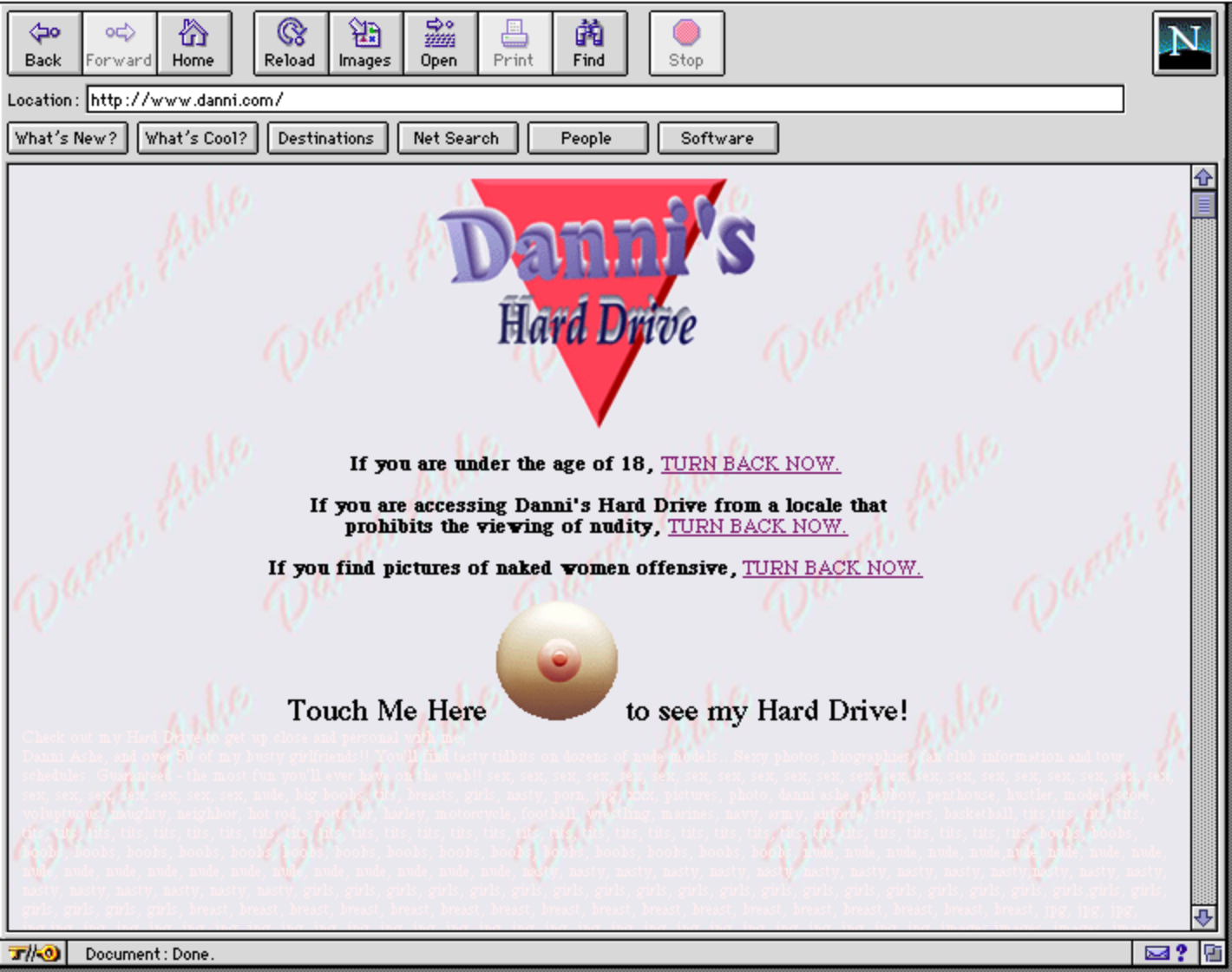

Although established producers like Playboy and Penthouse had the deep pockets to invest in the nascent network (they launched websites in 1994 and 1995, respectively), individual sex workers were also major players from the start. In 1995, Danni Ashe, a nude model and former erotic dancer, created Danni’s Hard Drive in direct response to her stolen images circulating on a BBS-like discussion board. Quoted in a 1999 Guardian article, Ashe explained that “after getting on Usenet and discovering how many of my pictures were being traded around, I made an introductory post to Alt.Sex basically saying hello and that I could be reached through my fanclub address.” She noted the keen irony of the “stern reply” she received from the board’s moderator “saying my ‘commercial postings’ wouldn’t be tolerated.”14

1995

Danni’s Hard Drive

After its launch in 1995, Danni Ashe’s website became the most popular site on the internet for two years. Source

If it were not for the adult industry, Cisco would never have sold so many routers or Sun as many servers as they have.

Barss, The Erotic Engine, 170.

Audacia Ray, Naked on the Internet: Hookups, Downloads, and Cashing in on Internet Sexploration (Emeryville, CA: Seal Press, 2007): 135.

Ray, Naked on the Internet, 180.

David Kushner, “Debbie Does HTML,” The Village Voice, October 6, 1998, 47.

Ashe’s site, which sold monthly memberships, was so popular that, for the first two years of its existence, it was the busiest site on the internet.15 Ashe was remarkably resourceful and enterprising; she later boasted that she launched her site with “$8,000 worth of equipment and an HTML how-to book.”16

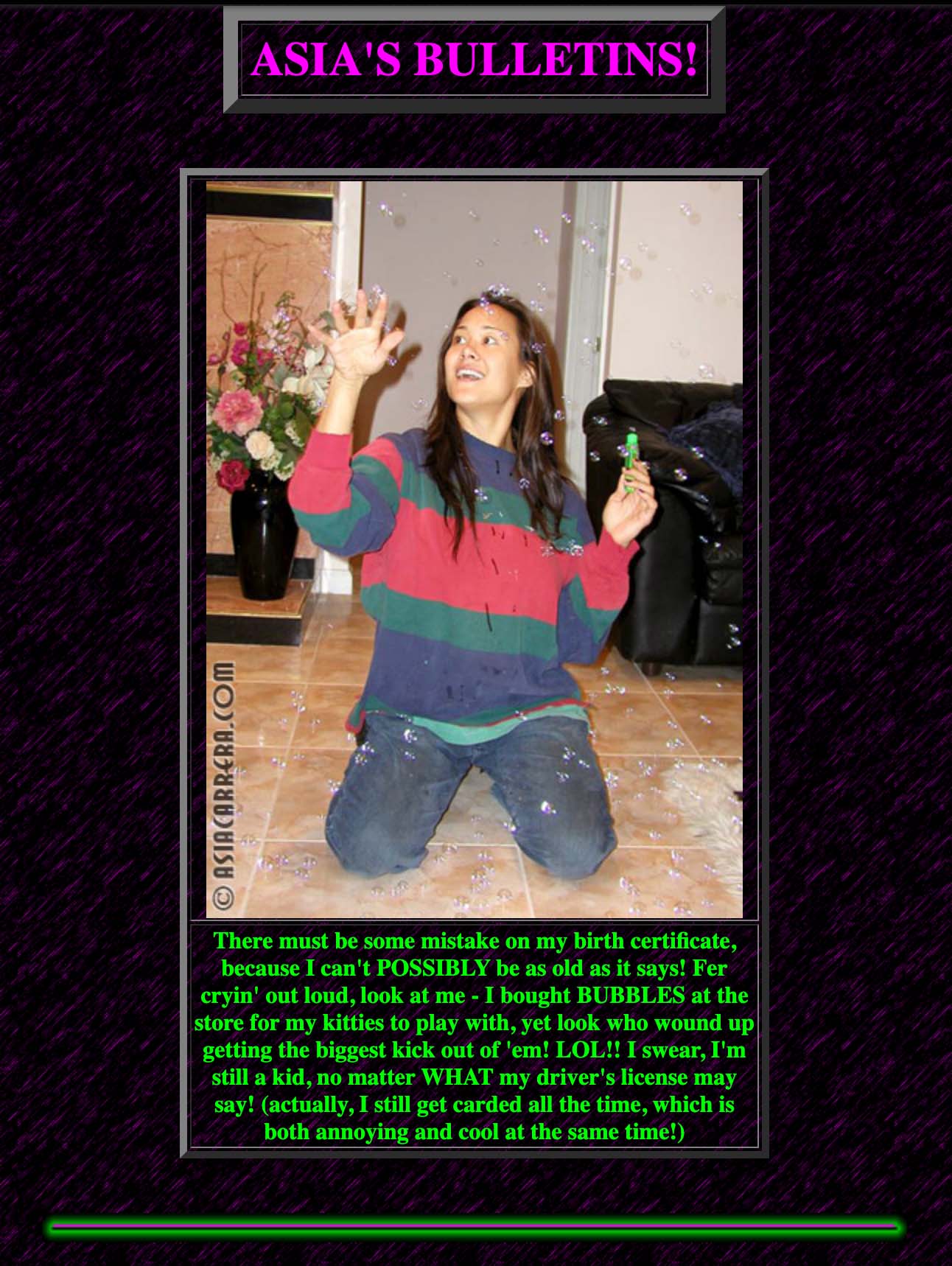

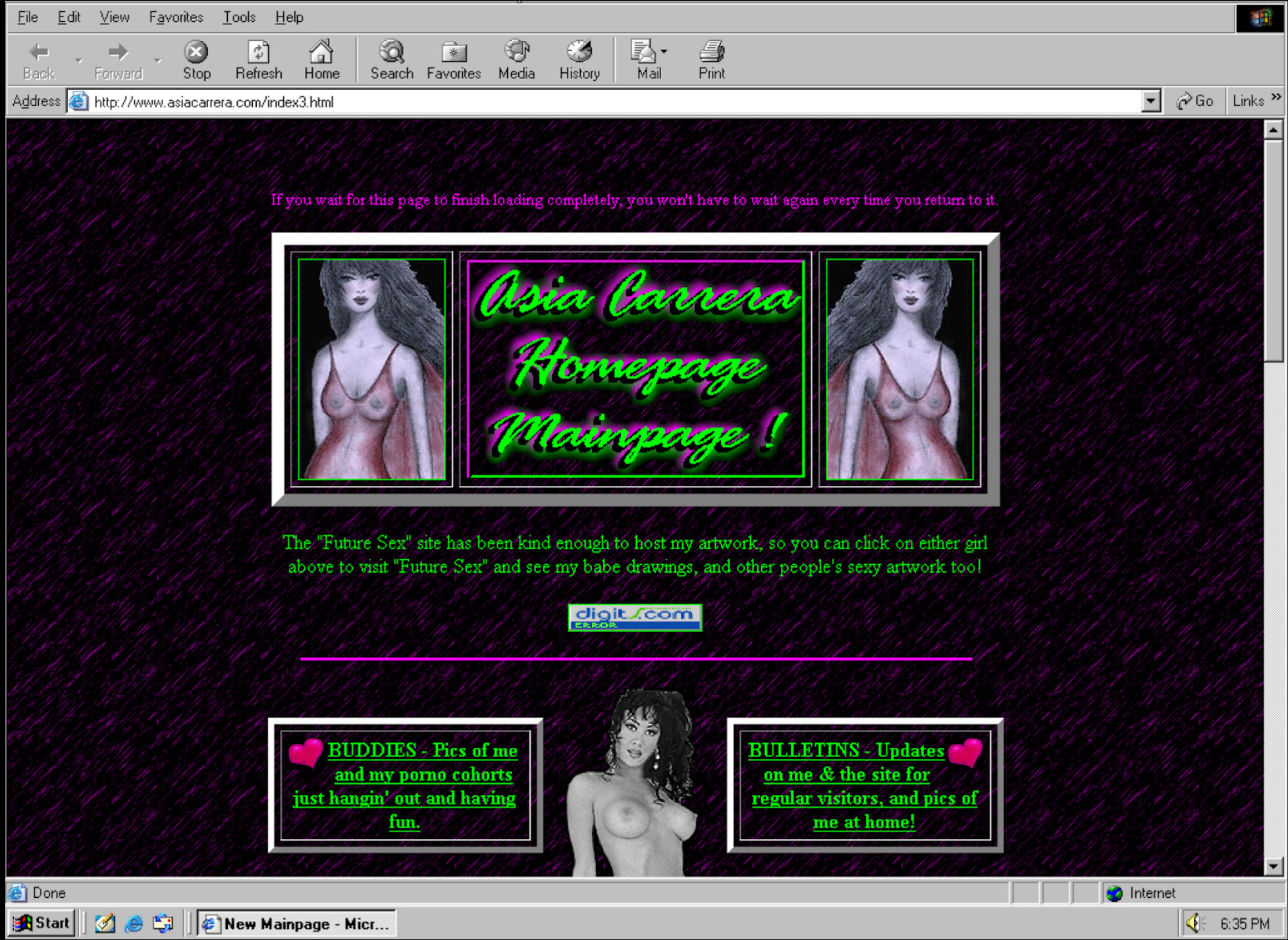

While Ashe’s success was widely reported at the time, she was far from alone. The first major woman-owned BBS was launched in 1995 by Catherine La Croix, a sex worker who entered the adult industry as a phone sex operator in the 1980s.17 By 1998, a Village Voice article took note of a growing trend, interviewing established porn stars Mimi Miyagi, Asia Carrera, and Vanessa del Rio, who were augmenting or replacing their film work with paid subscription sites. The article quoted a performer named Jenteal, who explained that “it’s trendy in the business to have your own Web site.”18

1997

Asia Carrera’s Homepage

Carrera revels in her technical prowess and quirky sense of humor: “I’m a 100% self-taught computer geek, and I take pride in running my whole site myself, from start to finish – because that’s the way dictators do things!” Source

The women profiled emphasized the independence and flexibility their self-owned platforms afforded them, citing benefits that would come to define the upsides of online work decades before most workers experienced them. Miyagi credited remote work with enabling her to have the child she fiercely wanted. Several women said the rise of AIDS pushed them to the relative safety of remote work—a benefit many white collar workers have been grateful to take advantage of during Covid-19. All relished the opportunity to control their working hours and conditions, self presentation, and, of course, profits.

With the Net, we have full control. We know how to program. We don’t have to rely on these men anymore. We rely on the girls.

As many of us today — from platform gig workers with algorithmic bosses to white collar workers with spyware-enabled company laptops — know too well, this autonomy would not necessarily last. In a revealing detail, the piece mentioned that industry heavyweight Vivid Entertainment had begun offering website services to their contracted stars —presumably, in exchange for some amount of creative and financial control.

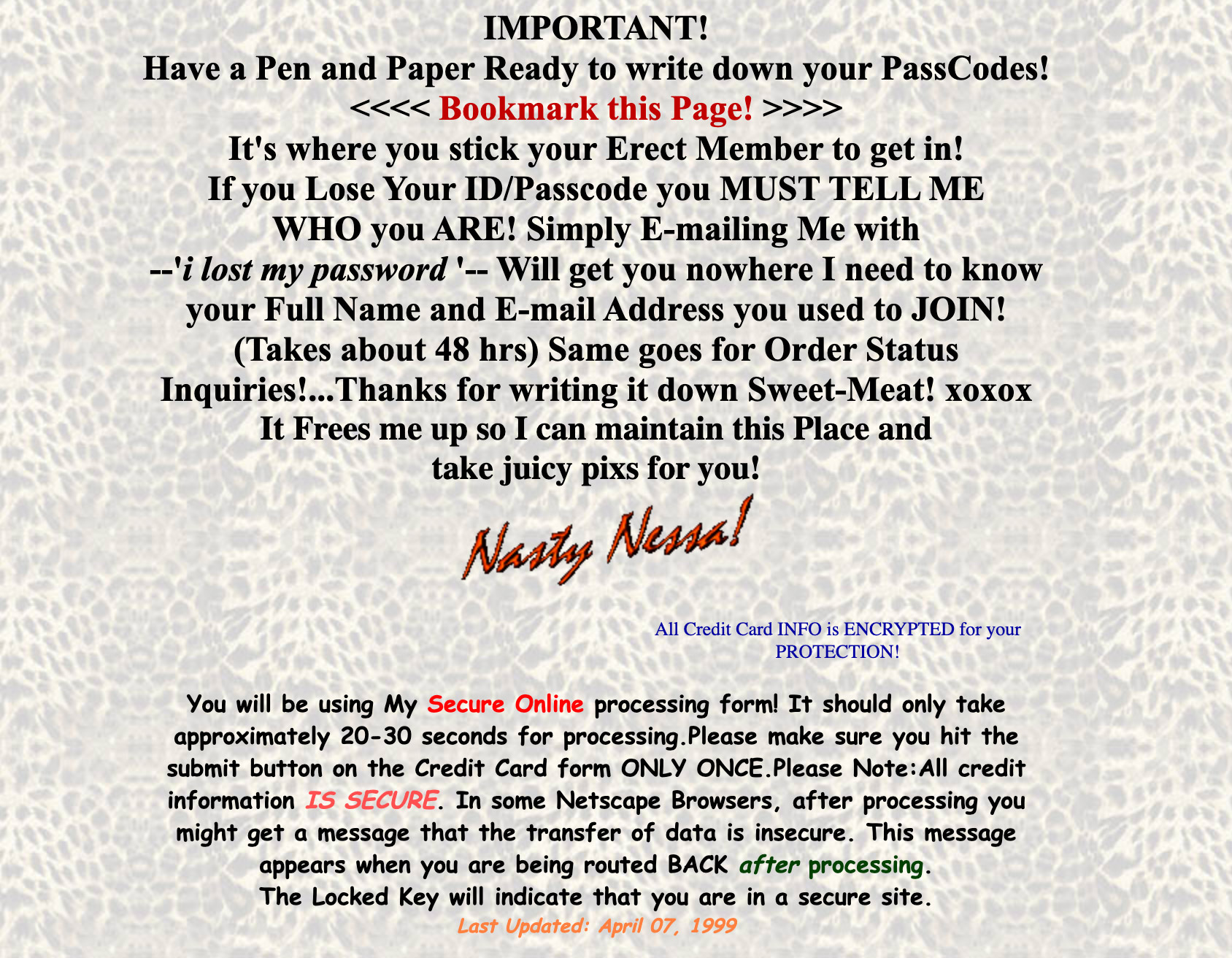

1999

Vanessa del Rio’s Official Site

On her site’s homepage, del Rio shares an exasperated, double entendre-laden tutorial walking customers through the unfamiliar process of signing up for a user account and entering their credit card information. Source

The adult industry is pioneering commercial activities on the Web, and the same gimmicks employed by adult pay sites today may be employed by your favorite online magazine tomorrow.

Barss, The Erotic Engine, 170.

Sara Silver, “Online Success Stories: Virtual Sex Makes Money, Transforms Technology,” AP News, June 17, 1997.

Before Google and Amazon, Ashe, La Croix, Miyagi, Carrera, del Rio and other adult industry early adopters invented or popularized technologies that would form the foundations of the commercial web. Real-time video was, unsurprisingly, of particular interest. Years before the 1999 debut of streaming video in Windows Media Player, Danni’s Hard Drive developed a proprietary version called DanniVision.19 In a 1997 AP News profile of Madeleine Altmann, the porn model, entrepreneur, and artist behind the adult site Babes4U, the word “streaming” is placed in quotes and defined for readers as “compressed, high-resolution images that appear to move naturally.”20

[I started] the first live streaming peepshow online on the internet in 1995. We also developed the technology to charge by the minute with credit cards. Few people know that it was a student at NYU and a programmer from Germany that thrust the internet to the next level.

Brooks, “The Porn Pioneers.”

Frederick S. Lane, Obscene Profits: The Entrepreneurs of Pornography in the Cyber Age (New York: Routledge, 2000): 70.

Barss, The Erotic Engine, 171–172.

Employing creativity, business savvy, and technical expertise, Ashe, Altmann, and their contemporaries dreamed up a host of new ways to make money online, including pay-per-click banner ads and real-time credit card processing;21 monthly site fees;22 affiliate marketing, where retailers pay partner sites for referrals; site traffic analysis, which allows sites to sell ads based on visitors and analyze search terms and traffic sources; and cookies, the code snippets that let sites track their users’ browsing activity.

Contemporary readers are, of course, well aware of the downsides to these developments. But surveillance capitalism aside, it’s clear that our prevailing narrative of internet history, which begins with Tim Berners-Lee and the US military and jumps to Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, and the rest of the tech oligarchs, erases the labor and innovation of gendered, racialized, and stigmatized adult industry workers.

When I think about sites like OnlyFans and the other platforms we currently use, another company charging the model for the fees is nothing new. It’s something that we’ve been experiencing since the beginning of the internet.

An industry takes shape

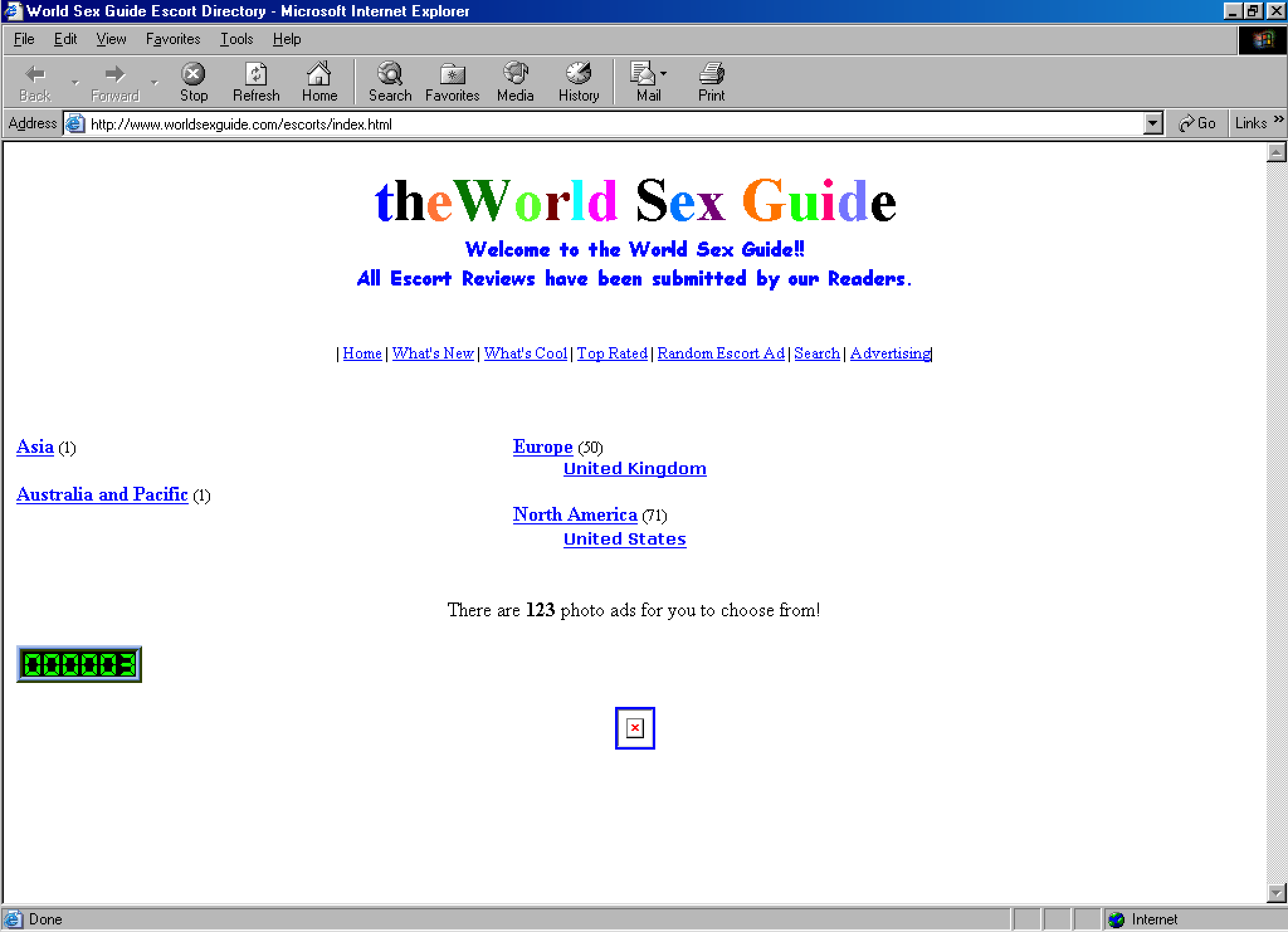

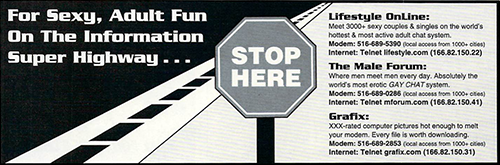

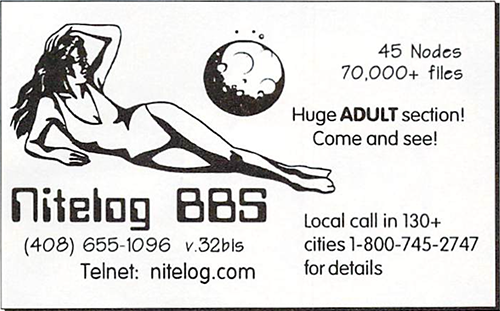

As early innovators proved the web could be monetized, an industry of intermediaries materialized to facilitate erotic labor online.

Susannah Fox and Lee Rainie, “Part 1: How the Internet Has Woven Itself into American Life” (Pew Research Center, February 27, 2014).

Sara Silver, “Online Success Stories: Virtual Sex Makes Money, Transforms Technology,” AP News, June 17, 1997

Frederick S. Lane, Obscene Profits: The Entrepreneurs of Pornography in the Cyber Age (New York: Routledge, 2000): 212.

Prominent adult film stars and a few tech-savvy workers proved there was money to be made, but the internet was still niche (in 1995, just 14% of U.S. adults were able to go online1). Access was limited to those with the time, skill, and capital to navigate considerable technical and financial hurdles — in 1997, Madeleine Altmann’s site ran on “$100,000 in phone lines and equipment.”2 The internet hadn’t yet begun to affect the day-to-day lives of most sex workers. Writing in 2000, the author of a book on porn entrepreneurs extolled the “quantum leap in the number of women who are controlling the use of their own images and reaping the economic benefits,” but estimated that perhaps “only 200 or 300 women and/or couples are running their own Web sites.”3

Sinnamon Love in Hacking//Hustling, “Digital Stimulation: Sex Invents the Internet,” 2022.

But that would soon change, as individuals and companies with money and technical expertise recognized financial opportunity. Although not unique to internet technologies — as Sinnamon Love notes, “where there are sex workers, there’s always going to be new investors,”4 — a web-specific industry emerged to bridge the access gap. Aspiring “webmasters” began marketing all-in-one packages that made it much easier for average workers to build and maintain an online presence.

Webmasters provided a way to work for a company and collect a paycheck without having very much experience or all the money for hosting fees.

2002

Webmaster Rocco comic

Courtesy Georgina Voss, private collection.

In parallel to the burgeoning webmaster industry, a constellation of services emerged to facilitate the complex, costly process of getting erotic images online. Companies offering image scanning, web design, web hosting and billing marketed their services directly to adult industries, while established industry players like Adult Video News built their own web teams.

ca. 1994-1999

Adult scanning services

Courtesy Georgina Voss, private collection.

2000

Graphic designer wanted, Adult Video Network

Courtesy Georgina Voss, private collection.

Frederick S. Lane, Obscene Profits, 70.

Patchen Barss, The Erotic Engine: How Pornography Has Powered Mass Communication, from Gutenberg to Google (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 2010), 168.

By the mid-’90s, the online adult industry was growing exponentially (its size was estimated at $2 billion by 19985), even as mainstream tech companies struggled to find profitable business models.6 However, in a now-familiar pattern, the tech industry took pains to erase its sex-tinged origins as it bid for wider acceptance and investment.

[Pornography is] one of the few industries actually making money through the Internet.

Bart Ziegler, “Banned by Comdex, Purveyors Of Porn Put On Their Own Show,” AP News, November 14, 1995.

In 1994, the giant computer industry trade show Comdex expelled its adult industry exhibitors, who had already been relegated to the show’s basement “with no-name companies that [sold] wiring, connectors and other mundane fare”7 and banned from displaying nudity or sexually explicit materials. When several exhibitors flouted these rules, Comdex’s organizers kicked them out, and, when they refused to leave, the conference literally pulled the plug, shutting off electricity to the entire floor.

Ziegler, “Banned by Comdex, Purveyors Of Porn Put On Their Own Show.”

The next year, software distributor Fay Sharp organized a new conference to host the excluded adult companies. In 1995, AdultDex debuted in a Las Vegas hotel steps away from Comdex, and with slightly later hours. Trading barbs in the press, Sharp accused Comdex’s chief executive Jason Chudnofsky of censorship, while Chudnofsky appealed to the industry’s mainstream aspirations, stating that “Comdex is a place where people show creative new products for the betterment of the industry. This is not appropriate.”8 Chudnofsky also noted that Comdex was giving up almost $500,000 in revenue by severing its relationship with adult companies.

I programmed this site because I got ripped off by my ex-webmaster & administrator guys.

As the adult industry fought for recognition, workers encountered familiar power dynamics in a new medium. Companies that profited from erotic labor enabled more workers to take advantage of the considerable benefits of working online. However, as Gabriella Garcia notes, technological barriers to entry meant that workers were still being exploited, often along axes intersecting with race and gender.

The gatekeeper of the technology was able to profit. Porn producers or webmasters took the opportunity of new technology to extract the labor of sex workers, without much changing in labor or gender issues. But once sex workers start grabbing this technology for themselves, you start seeing interpretive flexibility of use that moves away from extraction.

Over the next decade, webmasters and other intermediaries would become obsolete. And as new tools radically democratized internet access, workers quickly and creatively employed them to share information, find community, and demand their own recognition.

Visibility / Connection

V*s****ity / C*nn*ct**n

As the internet takes off, sex workers face the collapse of URL and IRL privacy — but also expand their communities, share information, and keep one another safe.

For workers, access facilitates independence

Throughout the late ‘90s and early aughts, more workers moved online and took control of their working conditions.

For workers, it’s easier to post ads, it’s easier to post content. And then of course, all of a sudden we have selfies. So we’re not relying on managers and we’re not relying on photographers to construct and then post our ads. It gives an entirely different level of independence for what working can be.

Technology like Macromedia’s Dreamweaver allowed sex workers and webmasters with very little coding experience to be able to edit templates and build a web presence.

One of the things that changed was our ability to work independently, to work without a manager, because we could reach out directly to clients.

Would-be Larry Flynts now require only a web-cam, video cameras to upload real-time images to a website, maybe a digital camera, and software ranging from shareware to a $100 commercial package… Where women operate a site, they control their participation, performance, and imagery.

It is a constant, treacherous walk of this line between the violence of visibility and the violence of invisibility. And I haven’t found a way around that. All we do is we keep strategizing and we keep doing what we can. For a lot of us, the risk assessment changes day to day, depending on what we need that day.

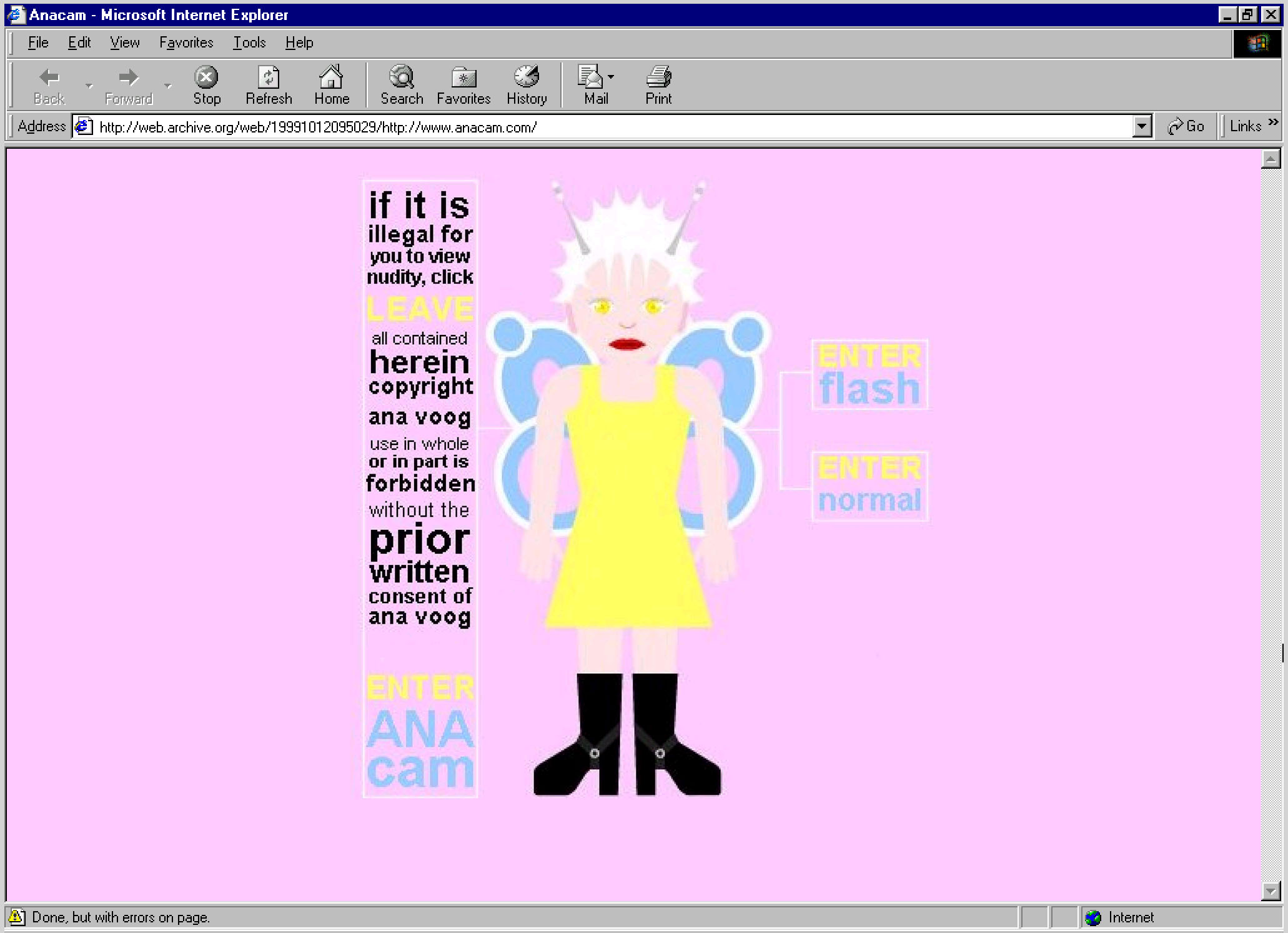

URL and IRL begin to collapse

As the web expanded, online events brought offline consequences, and vice versa.

As anacam, I began to experience almost immediately the sort of online bullying that happens to so many women online today. Being a single woman speaking her mind—while being naked, to boot—was a huge taboo. People would tell me that I should know my place. I was stalked and harassed.

Anonymity on the internet allows people to be their real selves, even if their real self is a troll.

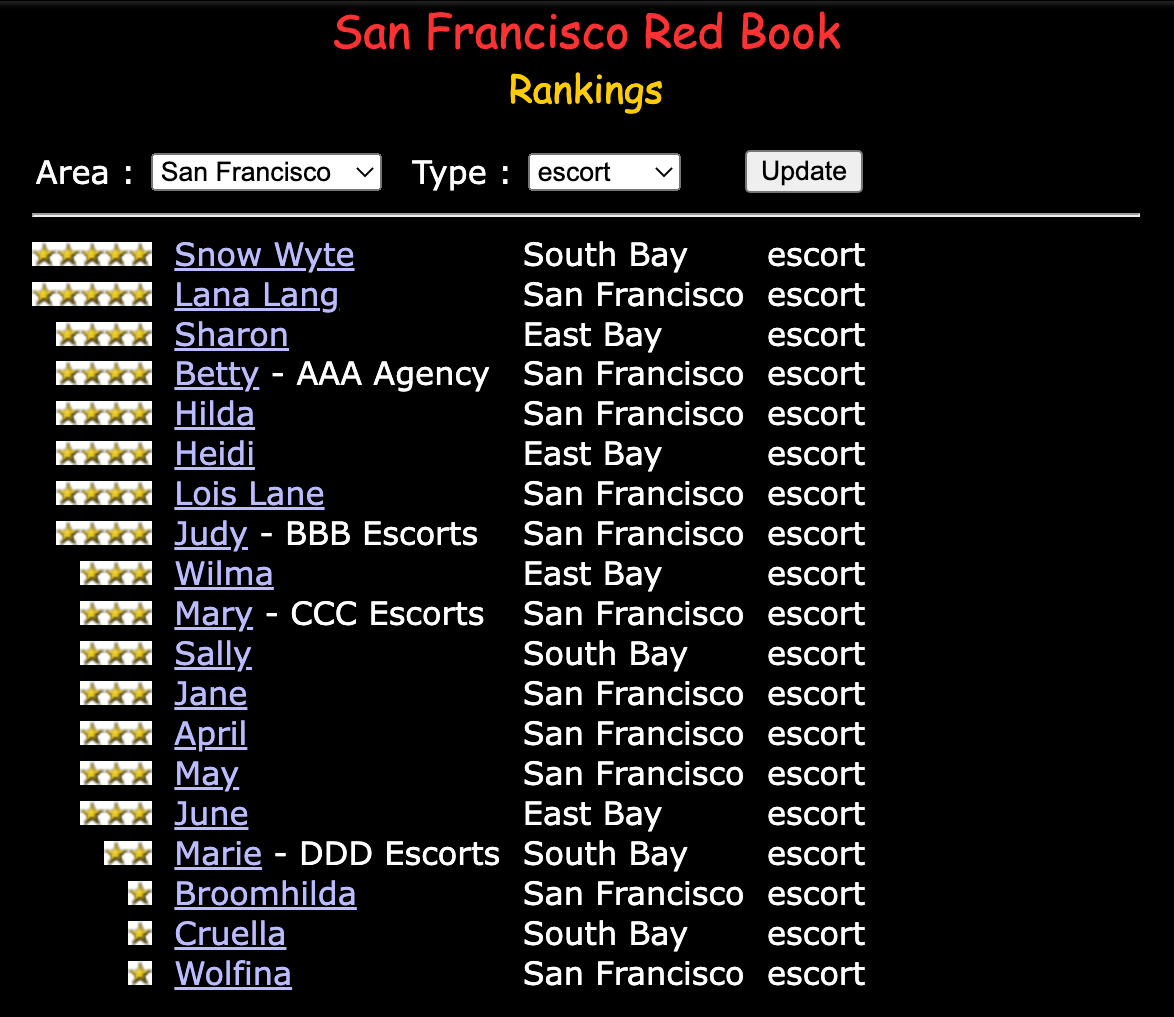

Many sex workers who hadn’t turned to the internet willingly were essentially forced online to combat false negative reviews which had the power to disastrously damage their income.

Quality-of-life crimes in the ‘90s prompted street-based workers to migrate to the internet. People didn’t want sex workers standing around in their neighborhoods, and they would get arrested for loitering or for working on the street. Newspaper ads, and later the internet, allowed a certain segment of privileged populations to be able to advertise very cheaply and work more safely.

At the time, the idea that someone could emerge out of this mysterious void and speak back to you was mind-blowing. But it requires emotional labor to be present for that interactivity. Nowadays, there is an expectation, and sometimes entitlement, that sex workers be available 24/7.

Increasingly, sex workers, and everyone else, face the pressure to have a personal brand that corporations can mine for data. We need to figure out how to perform authenticity, and there are pros and cons to that. A major pro is that the more you’re able to be yourself, the more opportunity there is to connect with the people who resonate with that. The con is that you’re always on, and you have to figure out what your relationship to yourself is when everything about yourself is potentially available for consumption.

The Internet has allowed for a massive shift as far as access goes, and the sex industry has therefore become more accessible to would-be workers and clients. The sex industry has also simultaneously become more private and more exposed, more professional and more of an identifiable culture.

Community spreads through new networks

Marginalized workers found each other online, sharing information, harm reduction tools, and personal and political narratives.

The internet provided a place for marginalized workers, who often feel isolated from one another because their work is stigmatized and criminalized, to connect.

Sex-worker-advertising sites are increasingly becoming online communities where people hang out to discuss different issues centered on sexuality, but the discussions also deviate from this topic.

There were early conversations about sex work in sex work-specific Usenet groups. alt.sex.prostitution was probably the biggest one of those. The first sex worker-only online communities, where we presumed we were just talking to ourselves, were on LiveJournal. A lot of the webcam girl community was focused around LiveJournal, but there were escort and stripper communities there, too.

[With new tools], sex workers are actually in control of the places where they can promote their work. And you see communal safety, people advertising for each other, figuring out ways to make sure there’s mutual aid.

We started creating these gallery pages that featured thumbnails of the models on your friends list. And then when someone would click that image it would take them to their website. So this was a really innovative way of being able to drive traffic.

Much of this innovation came in the form of harm reduction technologies. As low cost or free self-publishing tools opened up access and eliminated the need for gatekeepers like webmasters or production companies, workers moved existing safety tools, like bad date lists and customer screening techniques, online, and created new ones.

The popularity and ease of self-publishing on the Internet via blogs and websites has led to the rise of public bad-date lists and blacklists. This is due, in part, to the ease with which workers can put up and update their own sites.

We were certainly screening calls from the newspapers, but the internet really did allow you to access information in a way that we just didn’t have before. Being able to look up someone’s phone number, being able to look up someone’s address, being able to verify that the phone number someone was calling from was in fact the number to their office — these things were really a necessary component to being able to be safe.

This website is a tool, intended to help you from booking a no-show appointment, dealing with someone who doesn’t pay you what you asked, or any other negative experiences that may arise in this discreet, service-based world that we inhabit.

2007

Christian Sings the Blues

Christian Sings the Blues, an early blog run by porn star Christian XXX. Sinnamon Love credits Christian’s blogging with inspiring her to begin blogging herself. Source

Beginning with blogging, there was the ability to actually see into peoples’ lives from the perspective of a worker. There was a demystification and a humanization of experience that was also educational. I didn’t have any community in real life at that point in time. It was because of these digital personas that it even felt safe to consider it as a financial possibility, and also have this safety net and community of people that I literally never have seen in person.

Surveillance / Survival

Surv***l*nc* / Surv***l

As sex workers face algorithmic policing, digital gentrification, and censorship, new networks introduce new avenues for political organizing.

Sex Workers Built

The Internet

Today, they’re leading the fight against online censorship and discrimination.

How long can we afford not to listen?

take action

If you teach about the internet and technology Spend at least a few minutes talking about the central role sex workers play in developing and popularizing new technologies. You can use the materials gathered on this site, and in the Resources section below.

If you design or build social technology Learn to respect and prioritize sex workers’ skills and expertise, actively seek out and prioritize their perspectives, and compensate them accordingly. Many of the resources in the Sex work & technology section provide best practices, and some of the organizations in the Sex-worker-led groups section offer consultation services.

If you work, communicate, or organize online Seek out sex workers’ positions on internet policies related to privacy, autonomy, and safety. Follow and donate to the organizations in the Sex-worker-led groups section to support their advocacy, community organizing, and mutual aid efforts.

Resources

A non-comprehensive collection of resources to learn more and support sex worker-led activism, research, and creative expression

The basics

Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights

Sex workers Mac and Smith situate the sex worker rights movement and fight for justice within wider questions of migration, work, feminism, and resistance to white supremacy.

Juno Mac and Molly Smith, Verso Press, 2018

Book

Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work

A foundational text that dismantles myths about sex work and argues that separating sex work from the "legitimate" economy only harms those who perform sexual labor.

Melissa Gira Grant, Verso Press, 2014

Book

85 Ways to Make Sex Workers’ Lives a Little Easier

Writer, theorist, and erotic laborer femi babylon offers “some simple strategies for educating yourself and generally being less of a jerk about sex work.”

femi babylon, Vice, 2020

Article

We Too: Essays on Sex Work and Survival

Sex workers from across the industry complicate narratives of sexual harassment and violence, and expand labor conversations often limited to normative workplaces.

Edited by Natalie West, with Tina Horn, The Feminist Press, 2021

Book

Sex Work: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver

An excellent introduction to legal and ethical issues around sex work, policing, labor rights, and the fight for decriminalization.

2022

Video

Sex work and technology

Operator

An entertaining history of the rise and fall of commercial phone sex in the 1990s, with insights into building communication technologies in a stigmatized industry.

Wondery, 2021

Podcast

Algorithmic Bias Report

A community report finds that “social media algorithms adversely affect queer people, women, BIPOCs, people with disabilities, sex workers and plus size people.”

Salty Algorithmic Bias Research collective and the University of Michigan, 2021

Research

Smart Sex Worker’s Guide to Digital Security

A guide to the varied ways sex workers use communication technologies and navigate their benefits and threats, concluding with recommendations for stakeholders including technologists.

Global Network of Sex Work Projects, 2021

Research

OnlyBans

This interactive, browser-based game, created by a team of sex workers and allies, was made to “empathetically teach people about discrimination faced by sex workers online.”

Lena Chen and Maggie Oates, ongoing

Game

Posting into the Void: Studying the Impact of Shadowbanning on Sex Workers and Activists

Hacking//Hustling’s peer-led survey finds that online content moderation affects respondents’ livelihoods, free speech, and organizing efforts, and concludes with harm reduction suggestions for technologists.

Danielle Blunt, Emily Coombes, Shanelle Mullin, Ariel Wolf, 2021

Research

The Cybernetic Sex Worker

An essay tracing the perennial love affair between sex work and telecommunications while challenging the internet’s current state of censorship, surveillance, and bias.

Gabriella Garcia, 2021

Essay

FOSTA-SESTA

Erased: The Impact of FOSTA-SESTA & the Removal of Backpage

Hacking//Hustling surveyed sex workers about how their lives have changed post-FOSTA-SESTA, concluding that the law has had “detrimental effects on online workers’ financial stability, safety, access to community, and health outcomes.”

Danielle Blunt, Ariel Wolf, 2020

Research

Sex, Lies and Classifieds: The Fall of Backpage

An engaging guide into the weeds of the history, issues, players, and fallout around FOSTA-SESTA and related internet legislation.

RIP Corp, 2021

Podcast

Teaching about sex work

The Heaux History Project

A multimedia archival project exploring Black, Brown, & Indigenous erotic labor and sex worker histories.

Ongoing

Archive

Trains, Texts and Tits: Sex Work, Technology and Movement

A four-part course covering the history of sex work and tech in the US from the 1800s to today, with readings, videos and experts from the sex worker community.

Hacking//Hustling, 2021

Videos

Sex Work Centered Guide for Academics

This guide for college-level educators includes readings, covers ways to assess good and bad sources, and offers suggestions for study topics related to sex work.

Support Ho(s)e, 2020

Guide

Sex worker-led groups

European Sex Workers Rights Alliance

Sex worker-led network proudly representing more than 100 organizations in 30 countries across Europe and Central Asia.

Europe, Central Asia

Network

Desiree Alliance

Sex workers, health professionals, social scientists, professional sex educators working to understand the sex industry and its human, social and political impacts.

United States

Coalition

Black Sex Workers Collective

Amplifying the voices of Black Sex Workers by addressing their needs through peer support, legal assistance, housing and other basic needs assessment.

United States

Collective

HIPS

Advancing the health rights and dignity of people and communities impacted by sex work and drug use by providing non-judgmental harm reduction services, advocacy, and community engagement led by those with lived experience.

Washington, DC

Nonprofit

SWARM

Campaigning for the rights and safety of everyone who sells sexual service through skill-shares and support meet-ups just for sex workers, as well as public events.

United Kingdom

Collective

Hacking//Hustling

Collective of sex workers, survivors, and accomplices working at the intersection of tech and social justice to interrupt violence facilitated by technology.

NYC-based, global

Collective

Red Canary Song

A grassroots collective of Asian and migrant sex workers and allies, organizing transnationally.

NYC-based, global

Collective

Sex Workers Outreach Project (SWOP) USA

Dedicated to the human rights of sex workers and their communities, focusing on ending violence and stigma through education, community building, and advocacy.

United States

Network

BIPOC Adult Industry Collective

Upholding the voices of sex workers, in all our diversity, and protecting our health and human rights globally.

NYC-based, United States

Collective

Sex Workers Project at the Urban Justice Center

Destigmatizing and decriminalizing people in the sex trades through free legal services, education, research, and policy advocacy.

NYC-based, United States

Nonprofit

Contributors

This project gathers the words, ideas, and experiences of people whose identities encompass—but are not limited to—sex workers, artists, activists, organizers, and researchers.

About this project

I was inspired to use these words by Mindy Seu’s Cyberfeminism Index, and Seu, in turn, credits adrienne maree brown’s use of “gathered” in Pleasure Activism.

This website was written, facilitated, and gathered1 by Livia Foldes, an artist, designer, and co-founder of Decoding Stigma, a collective working to prioritize sexual autonomy as a necessary ethics question for futurists. It includes the words of many people, who are featured in the Contributors section and cited frequently throughout the text. It was coded with creativity and care by my partner in life and work, Andrew Lux. It grew from the urgent scholarship of Trains, Texts and Tits: Sex Work, Technology and Movement, a series of classes organized by Hacking//Hustling, who generously shared their knowledge and intellectual labor. And it would not exist without the thinking, writing, and research of writer, performer, poetic technologist, and fellow Decoding Stigma co-founder Gabriella Garcia, whose powerful ideas are central to our collaboration.

Sex Workers Built the Internet emerged while I pursued an MFA in design and technology at Parsons School of Design, and it addresses what I came to recognize as a large and problematic knowledge gap in the field. When sharing my work related to Decoding Stigma, I found it was necessary to spend a good portion of each presentation establishing basic information about sex work and its relationship with technology—information I was also unaware of until actively seeking it out. With this project, I aim to share a growing body of knowledge rooted in sex worker rights activism with a broad audience of designers, technologists, and educators for whom this information is both relevant and essential.

Research assistance — Sarah Epstein

Music — Harrison Pollock

Thesis advisors — John Sharp, Clarinda Mac Low, Jamie Lauren Keiles, Barbara Morris

Special thanks to the many individuals who shared their time and feedback (in alphabetical order) — Kendra Albert, Danielle Blunt, Adrienne Cassel, Melanie Crean, Chibundo Egwuatu, Pantéa Farvid, Vaughn Hamilton, Chaski No, Yin Q, Monica Sheets, Zahra Stardust, Georgina Voss, Emily Dall'Ora Warfield